Monday, February 23, 2009

How Sarbanes-Oxley kills initiative

I have long fulminated against the cultural impact of the Sarbanes-Oxley law's "internal controls" requirements (see, e.g., the last bullet in this post); my objection, heretofore expressed in generalities, is that SOX promotes process considerations above risk and results to such a degree that we are hurting the adaptability of American business. Occasionally readers have challenged me for examples. Sadly, most of my examples are confidential. They are also, one by one, petty, and therefore not impressive evidence in support of my larger argument. But the petty examples do add up, one on another, until the entire organization is thinking more about how to do a thing than what to do in the first place.

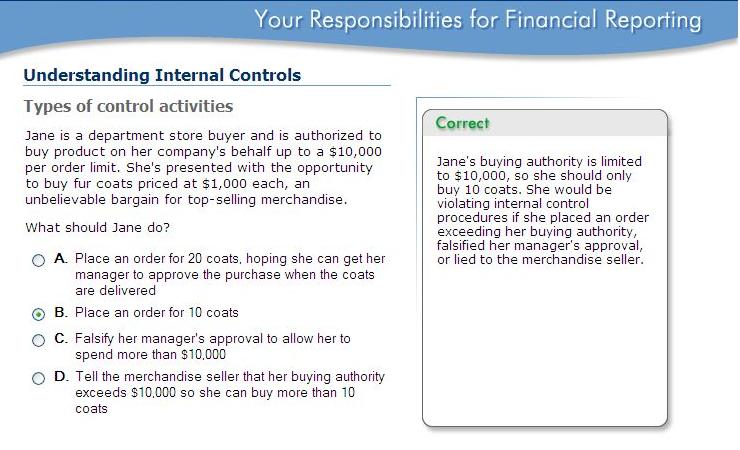

That said, today I stumbled across a great example of the nefarious influence of SOX. The picture below is a screencap from a web-based SOX training module that I was delighted to take this afternoon as part of our regular corporate compliance program. Read the question and proposed answers, and note that I have helpfully checked the correct one so that you can read the useful explanation. Commentary below...

Sadly, the menu of possible answers is missing the one that is actually correct, which is that Jane -- using her brain to think, rather than to follow an unthinking routine -- should go to her supervisor, explain the great opportunity to buy coats in volume at a discount, and request a waiver of her purchase authorization limit (or that the purchase be made by somebody with more authority). That is obviously what Jane should do, yet it apparently never entered the mind of the people who wrote this training session. That is bad news for the shareholders of the companies that employ the tens (if not hundreds) of thousands of American workers who have taken this module.

Now, you might say that a poorly drafted question in a training module does not ultimately impeach the SOX internal controls rules, and you would be correct. Theoretically, it would be possible to segregate duties and to teach SOX compliance without diminishing the willingness of rank-and-file employees to think out of the box, take initiative, and push for change. In practice, however, it is virtually impossible for at least two reasons.

First, most employees in most large companies will follow rules and procedures before they do anything else. If you pile up enough rules and procedures and cross-checks and sign-offs and multi-signature documents or "workflows" you will crowd out the small amount of brain space that most people have available for thinking creatively or laterally. People can only follow so many rules before they become rule-following automatons.

Second, any sufficiently burdensome process inevitably becomes an excuse for inaction. Rules are developed for the average case, not the exceptions, but businesses compete and make money based on their ability to deal with the exceptions quickly and efficiently. Unfortunately, many people will fail to deal with the exceptions because they lack the wherewithal -- ambition, energy, or bureaucratic intelligence -- to integrate rules for the average case with the facts of the exceptional case. The result is, well, failure.

Of course, you might argue that the prevention of financial catastrophe is such a great thing that the decline in adaptability and initiative in American public companies is a reasonable price to pay. My answer: All (or virtually all) of the American banks, investment banks, and insurance companies that catastrophically failed, or will fail, in the current financial crisis were in robust compliance with the internal controls requirements of the Sarbanes-Oxley law.

17 Comments:

By , at Mon Feb 23, 08:04:00 PM:

There is another cost to creativity and "thinking outside the box" that you do not mention. In my experience senior managers want creative thinking, but are not willing to abet such thinking. They want you to take risks and get things done, not let the "process" stop you, but are not willing to back you when the muck hits the fan (as it does from time to time when you take risks).

As a result, once burned (or observing a colleague burned) creative thinkers learn to use the process to protect them in the future to assure that management has officially signed on to an "outside the box" project. By its nature, the "process" discourages the manager from doing so, and thus initiative is lost.

By TigerHawk, at Mon Feb 23, 08:09:00 PM:

I agree with that. Good comment (although I like to think that I am not one of those senior managers, at least some of the 800 people who work for me probably think that I am).

By Mrs. Davis, at Mon Feb 23, 09:54:00 PM:

I think it goes back much farther than SOX, to the legalization of GAAP. I am not a CPA, so I can't cite chapter and verse, but at some point in the '60s the concept of principles that were applied with professional judgment to present financial information honestly and accurately was replaced with bright line rules that could be met while while not clearly or honestly presenting the truth behind the results of the rule based computation. SOX is the final step in this process, paving the way for CDSs and CDOs which I have never been able to understand as being more than bets.

I believe much of the severity of our current financial crisis is due to the utter lack of integrity in a system that relies not on people telling the truth but on them following rules.

By , at Mon Feb 23, 10:33:00 PM:

It's worth remembering Sarbanes-Oxley every time someone says the current crisis proves we need more regulation. We already got more regulation; what we didn't get, and are not going to get, is foresight.

By , at Tue Feb 24, 12:38:00 AM:

at some point in the '60s the concept of principles that were applied with professional judgment to present financial information honestly and accurately was replaced with bright line rules that could be met while while not clearly or honestly presenting the truth behind the results of the rule based computation.

What you speak of is standard government thinking. Judgment can't be permitted because using judgment implies there may be bias or unfairness. Hence bright line rules so you can demonstrate per se evidence of fairness and truth. The rules were not created with the intent to hide malfeasance, though of course they do that. It's no different than rigging the rules of a government contract bid to favor your cronies while evading the purpose of open bidding laws. Form has been elevated over substance.

By , at Tue Feb 24, 08:15:00 AM:

If you look at the SOX Act as a whole it's a very rushed piece of legislation -- legislators didn't even bother to reconcile duplicative provisions in the House and Senate versions. That's why public companies actually have to certify their financials twice -- Section 302 and Section 906 are largely duplicative. The SOX Act raised already hefty criminal penalties to ridiculous heights -- you can now get more years in jail for shredding a document than for attempting to kill a witness.

SOX Act requirements for internal controls can be traced to requirements put on banks in the 1980s. Back then there was a concern that even a small bank could be a threat to the financial system -- and there was evidence to support concern over such systemic risk. For years some of the extreme regulators at the SEC wanted something similar for public companies -- and got their chance to push for adoption in the panic following Enron and Worldcom.

This is overkill, because a single public company doesn't present the systemic risk of a bank. It's especially hard on small public companies, where the added cost burden can meaningfully reduce net income, and because some of the processes that the auditors want assume levels of internal staffing that a GE already had. In hindsight, Enron and Worldcom proved to be exceptional and isolated.

Link

By , at Tue Feb 24, 08:34:00 AM:

My brother and I both work for the IT division of the same company, a large multi-national corporation, although we work in two different departments and do two different jobs. We were talking the other night about our jobs and agreed that thanks to SOX and the many internal procedures, initiative is being stifled. It's almost as if we spend most of our time being bureaucrats instead of what we were trained to do.

By , at Tue Feb 24, 08:57:00 AM:

Tell me the rules and I will engineer a work around.

By , at Tue Feb 24, 01:46:00 PM:

I don't think this establishes a relationship between SOX and stifled initiative. That is, you don't show that the regulation itself, and the requirements it imposes, stifle worker initiative.

I'm no expert, but it seems to me that SOX simply requires accurate reporting of financials. One way it does this is by requiring redundant internal controls on financial decision-making within firms. So SOX may require Jane's firm to control how much of the firm's assets Jane can individually control, it does not keep her from thinking creatively--only her own incompetence or the firm's management can do this.

To be sure, regulatory frameworks usually increase costs to individual firms--someone has to monitor Jane's department and give the banal tests you describe. These costs, however, often bring benefits (e.g., increased market information, limits to risk, dispersion of corporate power) that arguably make markets more efficient in the aggregate.

Unless SOX requires specific procedures that limit action by employees--such as placing limits on what each worker can spend--blaming the law for stifled initiative and inaction points the finger in the wrong direction. If a firm piles too many rules on workers, refuses to support creative thinking, or permits workers to use government regulation as an excuse for inaction, it is management, not government, that is to blame.

Many large organizations do become rule-bound, but many do not. You won't find more rules--or more individual initiative--than you do in the US Military.

By TigerHawk, at Tue Feb 24, 02:18:00 PM:

I'm no expert, but it seems to me that SOX simply requires accurate reporting of financials.

Sadly, no. The requirement for public companies to publish accurate financial statements has been clear and uncontested since 1934. SOX requires that the business of the company be run in such a way as to guarantee that the process to develop financial statements is "under control." That concept, in turn, invokes a vast body of academic literature about "internal controls," which might make sense for very large companies with little need to move quickly but which make no sense for much smaller companies. Now, SOX further requires that public company auditors pass on the state of the "controls" in addition to the financial statements themselves. Post SOX, it is possible to have entirely true and correct financial statements and still flunk your audit. Many companies are in this situation. Now, you might then argue that the "problem" is that the accounting firms have chosen to interpret the requirements of SOX in a certain way that is very burdensome, and you would be right. Unfortunately, however, that interpretation is also a creature of SOX, which established a creature known as the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, or PCAOB. The PCAOB audits the auditors, and in my experience the fear of a PCAOB audit drives auditors to take conservative positions on such things as control procedures. This top-down conservativism then gets translated into corporate culture via web training and internal audit.

As for your last point, that you will not find more rules or more individual initiative than in the US military, I would not know. My father, however, told me stories from his years in the Navy in the 1950s, and the theme seemed to be disregarding the rules. When they needed to fix something, instead of dealing with the union work rules they gave a couple of the workers a case of small arms ammunition to do the work after hours. And so forth. I am sure things have changed a lot since then, but I do suspect that even with all the rules the military does not have the same level of "internal audit" as has been imposed on public companies. If it did, there would not be all the problems with procurement scandals and the like. Indeed, the giant pile of money that seems to have vanished in Iraq without an audit trail is evidence in support of my point.

By , at Tue Feb 24, 03:02:00 PM:

your example is pure BS. the correct answer is go to the next level of authority to sign off on a higher purchase ie her supervisor. this isn't rocket science

By TigerHawk, at Tue Feb 24, 03:19:00 PM:

Anon - I thought that is what I wrote (see the parenthetical). That option is not available in the training module, though.

By , at Tue Feb 24, 04:31:00 PM:

OK. So besides accurate financials, SOX requires a certain level of process, which is itself (conservatively) audited by the SOX-created oversight board. You still have made no case that this stifles innovation and creative thinking in some way.

One of the control procedures that Jane's firm has imposed is her purchasing limit. The question tests whether the worker understands that three of the possible answers would amount to a violation of this particular procedure. Unless SOX prohibits exceptions to internal controls like the one in the question, your example says little about how much the law proscribes employee behavior.

Poor web training and internal audit procedures can socialize workers into a bad corporate culture. But unless SOX mandates specific web training materials or particular internal controls, I would argue that the fault is management's for implementing its internal controls poorly--by choosing stupid web training questions, for example. It is not an automatic result of government regulation.

I brought up the military as an example of a large organization, with a rigid hierarchy and stringent rules, that nevertheless permits and even encourages creative thinking. I did not intend to associate innovation, creativity, and initiative with greed, corruption, or breaking rules. When you say innovation, I think "find more efficient ways to do things," not "how can I take shortcuts or steal without getting caught." If you think "innovation" and "corruption" are the same thing, perhaps you are right.

By TigerHawk, at Tue Feb 24, 05:32:00 PM:

Mr. Scott -

I was not trying to make a comprehensive evidentiary case for my point in this post. It was just an editorial comment. No doubt there are all sorts of good arguments for the auditing of internal controls; otherwise, they would not have such a following among academic accountants and other experts. Also, you are no doubt correct that some companies implement SOX controls more intelligently than others. All of that said, though, I stand by these points, evidence or lack thereof notwithstanding:

1. The internal controls requirements of SOX have worked a significant cultural change in American business that shifts the proclivities of American business toward more bureaucracy and slower decision-making.

2. The training module above is a canned program used by (I understand) many large public companies. Stupid as it is, it is widely disseminated and is teaching, in this question at least, risk aversion to the point of pathology. No, this is not the government's "fault," but like all excessive responses to regulation it is fairly predictable.

3. Regulation does not merely affect the specific thing it is supposed to regulate. It effects cultural change. Over time, different people will be attracted to public companies or repulsed by them than in the past. The post-Enron law and regulation has become such a load that I literally do not know a single senior executive of a public company that would not prefer to work for a private company, even at a cut in pay. That is a sea change, and not necessarily a good one for public stockholders.

4. SOX compliance sucks up a great deal of brain space so it crowds out real thinking except at the very top of the company (where executives do not really have to comply with SOX other than to set the "tone"). SOX 404 is also the "opiate of the compliance officers," meaning that it confers a false comfort over risk. People are expending so much throught on compliance that they are (undoubtedly) spending less time actually managing substantive risk. I repeat the point I made earlier: The financial mess we are now in developed under SOX controls, in companies that had spent millions (if not billions) to comply.

By , at Tue Feb 24, 10:41:00 PM:

1. More bureaucracy and more deliberate decision making will make America business stronger if it enables more thorough risk evaluation and careful implementation of innovative thinking.

2. Excessive response to regulation only comes from large, cumbersome organizations that accept training modules just because they are "widely disseminated."

3. Regulation that causes cultural change away from leaders who run their firms the way Enron's did is a good thing, and public stockholders who think that is how investments work need to take another look.

4. SOX compliance carries costs, but it is not clear that anyone cared about managing substantive risk at any rate. The firms that created the mess we are in did so under a government that did not enforce SOX effectively, so they got away with it. This is not the fault of SOX, but of the managers that ignored or gamed the system, and the regulators that allowed them to do so.

If you don't mean to make an "evidentiary case" for your assertions, why make them?

By , at Tue Feb 24, 11:00:00 PM:

More bureaucracy and more deliberate decision making will make America business stronger if it enables more thorough risk evaluation and careful implementation of innovative thinking.

This is nonsense. Innovation is almost by definition devoid of bureaucracy and deliberation. Change is not created by committee.

By TigerHawk, at Tue Feb 24, 11:00:00 PM:

If you don't mean to make an "evidentiary case" for your assertions, why make them?

Dude, it is just a blog post, not an academic paper. I was making one little point. As I said, I cannot discuss virtually all of the examples I have seen up close because they are, not surprisingly, confidential. I am the CFO of a public company, and have been the general counsel of two public companies, and started in life as a securities law. My opinions on this subject are not only backed by personal experience, they are very widely-held opinions. That is certainly not a reason for you to accept them (I would not dream of asking you to take them on faith), but many of the readers of this blog are also corporate lawyers and executives and the argument resonates with them.

As for your enumerated points:

1. Correct in theory, but rarely true in practice. That's my experience, your's may be different.

2. Perhaps that is true, but "large" is a lot smaller these days than it used to be. SOX has a much bigger impact on smaller public companies than larger ones, which were generally more bureaucratic all along.

3. No doubt, but the number of companies run the way Enron was is very small. We are regulating and imposing costs on thousands of companies to prevent a rare event. That regulation is not only costly, it is distracting. It may well prevent one harm, but it allows many others to go through.

4. You are just wrong on this point. SOX was enforced against the big financial companies as well as it possibly could be enforced (at least on average). The top accounting firms, under tremendous scrutiny and risk of liability, audited process as best as they could. And, in any case, my point was not that the financial crisis was the "fault" of SOX. Rather, it was that SOX was aimed at a very different problem (detection and prevention of fraud, not systemic market risk), so it missed the big kahuna. Like most armies, SOX was designed to fight the last war.