Thursday, August 31, 2006

Elephant bulls

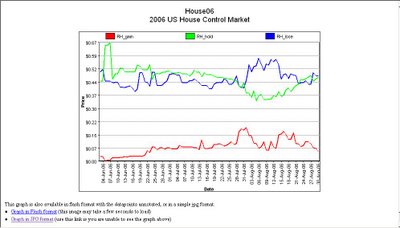

I dropped by the Iowa Electronic Markets for the first time in more than a month, and was surprised to see that the Republican House "hold" contract (the green line below) has risen significantly in price in the last three weeks.

What accounts for the improvement? Fidelity to history requires me to notice that the price of the Republican "hold" contract began to rise on August 10, the day the world learned of the foiled al Qaeda plot to blow up transatlantic flights, but it did not began the steep part of the rally until August 17, the day Judge Anna Diggs Taylor ruled that federal courts could veto wiretaps of terrorists who troubled themselves to conference in a "U.S. person." Mere correlation, or cause and effect? You decide.

(1) Comments

The conservation of the National Parks: It's Bush's fault

On page A16 of today's New York Times, we learn that the Bush administration has decided to sacrifice the environment on the alter of big business. Not.

Ending a yearlong debate over its management and guiding philosophy, the National Park Service is about to adopt a policy emphasizing conservation of natural and cultural resources over recreation when they are in conflict. Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne is expected to announce the new policy on Thursday.

The new regulations on park management give barely a nod to most of the concerns of the recreation industry and its Congressional champion, Representative Steve Pearce, Republican of New Mexico.

Thought experiment time: If the decision had gone the other way, would the Times have run the story a little closer to the front than page A16?

BONUS: GreenmanTim asks in the comments whether this might be part of a pattern:

Not having a paid subscription to the NYT, nor yet a regular reader, I cannot comment on this particular article, but would pose a test. How did the paper cover the August 17th signing of the new Pension Act? Any mention of the extremely positive incentives for donating conservation easements it contains(notwithstanding that they sunset in two years)? We in the land protection game are feeling pretty good about it - good enough for some of us to give CWCID to folks with whom we often are at odds politically. But we seem to be the only ones highlighting this aspect of the 900 page bill - after all, it's one of our core issues. Did the NYT cover it, and if not, do you suppose it was because they didn't catch it in those 900 pages or because, well, they'd have to acknowledge Senator Rick Santorum, as I felt in all fairness I should do on my blog, for his indispensible support in passing these conservation incentives? Doesn't mean I hope he gets reelected, but still...

I admit, Tim's post on the new conservation easement provisions is the first I've read on the topic.

The language of the August 17th Pension Bill raises the federal income tax deduction a landowner can take in any given year for donating a permanent conservation easement from 30% to 50% of their income (100% of their income for qualifying farmers and ranchers who donate agricultural easements), and extends the carry forward period for an easement owner to tax deductions from 5 to 15 years. This incentive means that there may be better economic outcomes for more willing easement donors than an outright sale of their land for development. It also means that land trusts and conservation organizations who cannot compete toe to toe in the open market with real estate developers have something of real, tangible value to offer that developers cannot: the ability to preserve a legacy on land you still own and a better bottom line for the landowner than a full fair market value sale.

Did the press bury an important victory for the environment because it doesn't want to give Rick Santorum favorable publicity? Say it ain't so!

(1) Comments

The problem with the "fabulous" economy

Regular readers know that I am a big booster of the American economy, and in particular its fluid labor markets. I know from managerial decisions that I have made why the United States creates a lot of jobs and growth and why Europe does not. My abiding affection for the creative destruction of American capitalism does not, however, mean that I drink the Kool-Aid down to the very last drop.

Case in point, the economically optimistic post du jour. Messers. Reynolds and Hinderaker, two men with whom I agree eight or nine times as often as I disagree, both linked to Engram's worthy post, "Americans hate their fabulous economy." Engram does a great job of showing how strong our economy is in the aggregate and that its performance diverges from the collective perception of it as measured by public opinion polls. How to explain this divergence? According to Engram, it is because reporters who write on the economy don't provide enough data in useful charts. I doubt it.

The problem with Engram's post is that it does not respond to the primary lefty criticism of the "Bush" economy, which is that real wages for the average Joe -- people who are not in, say, the top decile -- have been flat to down. If we look at The New York Times as a suitable proxy for "lefty criticism" -- anybody got a problem with that? -- we see a typical story from Monday's edition, "Real Wages Fail to Match a Rise in Productivity." Money graphs:

The median hourly wage for American workers has declined 2 percent since 2003, after factoring in inflation. The drop has been especially notable, economists say, because productivity — the amount that an average worker produces in an hour and the basic wellspring of a nation’s living standards — has risen steadily over the same period.

As a result, wages and salaries now make up the lowest share of the nation’s gross domestic product since the government began recording the data in 1947, while corporate profits have climbed to their highest share since the 1960’s....

Until the last year, stagnating wages were somewhat offset by the rising value of benefits, especially health insurance, which caused overall compensation for most Americans to continue increasing. Since last summer, however, the value of workers’ benefits has also failed to keep pace with inflation, according to government data.

At the very top of the income spectrum, many workers have continued to receive raises that outpace inflation, and the gains have been large enough to keep average income and consumer spending rising.

Not being an economist, I am hard-pressed to pick apart the data in the linked article. If Engram or another economist can do so, I'd be very interested. I do understand the superficial retorts, however. Yes, family incomes have continued to rise -- slightly -- because people are working longer hours, and, yes, total compensation keeps going up because the "value" of health benefits keeps going up, but neither of those qualifications is going to make the average wage earner happier no matter how thoroughly charted in newspaper articles.

Now, I am not proposing that the federal government do anything about this. I tend to think that these things revert to the mean, and that American workers will capture a larger percentage of GDP in the future, probably the near future, than they did last year. But I don't think that champions of today's economy -- and I include myself among them -- should pretend that the average guy is garnering the benefits of economic growth at the same rate that he did during the Clinton years. While I do not doubt that the media is tougher on the economy today than it was during the Clinton years, real wage stagnation is a more likely explanation for the sour public mood than a vast mainstream media conspiracy.

MORE: Glenn linked back, and had this to say:

Hmm. Maybe. But two observations: One, the shift from satisfaction to dissatisfaction is awfully abrupt, and comes when Bush was elected. Wages can't stagnate that fast, but media coverage can shift tone that fast. Two, I keep hearing about real-wage stagnation, but everyone I know who has a business complains that they can't get enough decent help even when they raise pay, because people are always leaving for better jobs. That may be a local phenomenon or something, but I'd like to see something that accounts for worker mobility, too.

Well, "hmm, maybe." The abrupt shift from satisfaction to dissatisfaction may have tracked Bush's election, or it may have tracked the collapse of the stock market, particularly the NASDAQ, starting in March 2000, and the weakening of the economy starting in early 2001. See the chart below, which shows quarterly GDP real growth by two different measures:

Eyeballing the table, it is hard to deny that things got soft in a hurry after Bush's election. It may have been Clinton's "fault" to the extent that fault can fairly be found, but I'm not sure that the rapid souring of the national mood did not reflect genuine economic problems. The question is, why didn't the national mood recover along with the economy, and I persist in thinking that the stagnation of real wages is a big part of the explanation.

I, like Glenn, also know a lot of people in business who complain that they cannot get enough "decent" help. In fact, I would be one of those people if I hung with Glenn. But there are two or three reasons why the shortage of good employees does not necessarily mean that the national mood about the economy is invalid, or somehow a creature of bad economic reporting. First, the sum of anecdotes is not data. Much as I would like to generalize from my own experience to the economy writ large, it is not particularly valid. I am also prepared to believe that the economies of Knoxville and Princeton are both quite a bit stronger than the national average, which may make good workers particularly scarce.

Second, the shortage of "decent" help is not easily remedied by paying more money. A lot of the time there are just not good people available at any reasonable price. Sure, you can lure a specific person away from a competitor by offering a huge pile of money, but that is a solution that works only in anecdotal cases. The ugly truth is that there is a huge mismatch in our labor force between the skills business needs and those that are available. The people without skills know that, and it both frustrates them and makes them unhappy. That leads to the third point: if you are basically unskilled labor, or have skills that are easy to pick up, it is very hard to increase your wages even when the wages of more educated employees are still going up. Yes, companies have been paying up for educated white collar workers, but they are not giving basic production employees wage gains much above the rate of inflation. Most companies target a corporate rate for their annual increase in compensation expense -- including health care benefits -- at no greater than the rate of inflation. If you hand solid real increases to your best employees to keep them motivated and shovel another big pile out the door to pay for health benefits, you make up for it by giving little or no increase to many other employees. Based on my admittedly anecdotal experience, I would guess that companies are differentiating among their employees much more aggressively now than they were even five years ago. A lot of employees get annual wage increases of less than 2% to "make up" for bigger increases to workers in high demand.

I have also received comments and emails with additional criticisms, all of which may be true around the margin but none of which strike me as dispositive. Some people have observed that "average" real wages may be stagnant because of a big influx in entry-level workers that would bring down the average without the circumstances of any individual employee worsening. Of course that is possible, but I oversee human resources at a pretty big company and have not read or seen evidence that the influx of entry-level workers in the last five years is manifestly greater than in 1995-2000. If there has been I stand corrected. Other people observe that the official inflation rate may be overstated by various measures, including that it does not adjust for the "Wal-Mart" effect on actual consumer prices, and that government statistics do not reflect the true purchasing power of the working class. See, e.g., Virginia Postrel's column in the current issue of Forbes. Far be it from me to deny any of this, but most of the gains Postrel cites have accrued over a period of decades. Yes, it is much better to be in the American working class today than in 1970. But that doesn't mean that it is better to be an average American wage earner today than in 1999, and that is the relevant period in Engram's post.

This is obviously a frustrating exchange, because I am a huge bull on the United States and its economy. I never want to talk down our economy, which I believe has been incredibly strong, especially considering the circumstances that have prevailed since 2001. However, I do believe that financial discipline inside American corporations, soaring healthcare costs, a growing tendency of employers to differentiate sharply among employees, and much higher gasoline prices (compared to 2000) have together wiped out wage growth for a great many people. One need not indict the Bush administration's "management" of the economy or even its tax policy to recognize that wage stagnation may account for a big part of the public's negative feelings about the economy.

BONUS: A commenter points to the latest news on this subject from the New York Times, which seems to support the idea that wages remain low as a percentage of GDP but will eventually revert to the mean:

Perhaps the biggest surprise in today’s report was a surge in wage-and-salary income during the first half of this year. Between the fourth quarter of last year and the second quarter of 2006, it grew at an annual rate of about 7 percent, after adjusting for inflation, up from an earlier estimate of 4 percent, according to MFR, a consulting firm in New York.

As a result, wages and salaries no longer make up their smallest share of the gross domestic product since World War II. They accounted for 46.1 percent of economic output in the second quarter, down from a high of 53.6 percent in 1970 but up from 45.4 percent last year.

Total compensation — including employee health benefits, which have risen in value in recent years — equaled 57.1 percent of the economy, down from 59.8 percent in 1970. Still, compensation makes up a larger share of the economy than it did throughout the 1950’s and early 60’s, as well as during parts of the mid-1990’s and the last couple of years

Again, I'm not facile enough with these numbers to pick them apart, but it does seem to me that if wages and salaries are just above their smallest share of GDP since World War II we should not be surprised if people who depend on wages and salaries are less than effusive about the direction of the economy.

(16) Comments

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Will declining gasoline prices save the Republicans?

Until yesterday, I had gone ten days without buying gasoline because I was holed up in a camp -- such as the one at right -- in the Adirondack woods. By the time I emerged, the price had fallen significantly. Traders think that they could fall below $2.50 per gallon by November.

If gas prices fall fast and far enough, will it be in time to bail out the Republicans?

(9) Comments

Bill Frist gets some good reviews

Back in November the Senate Republican Conference gave me the opportunity -- along with a few other bloggers -- to meet with six or seven leading Republican senators, including several who have obvious presidential ambitions. At the time I wrote this about Bill Frist:

Senator Frist was very impressive. He spoke very briefly, leaving lots of times for questions, and stepped around the podium in front of us to speak to us very directly and respectfully. He is obviously a man of great interests, knowlege and depth. Whether he has the personality to make a good president remains to be seen, but by my measure he is much better prepared today for the presidency than any of the other Senators who appeared before us.

It isn't surprising that I would like Bill Frist, in that I am fairly moderate in my right wingedness and easily seduced by book learnin'. Bill Frist's challenge has always been the red meat conservatives; one gets the sense that they regard Senator Frist as a bit PNQLU*. I was therefore interested and encouraged to read that John Hinderaker came away from his meeting with the Majority Leader with substantially the same impression that I had last November. Indeed, if I were forced to choose today, I might very well support Bill Frist for the Republican nomination. Perhaps that is because he is the only candidate for the nomination about whom I do not have some specific reservation, and perhaps that will change. At the moment, though, Bill Frist has my support until he loses it.

Senator Frist's blog is here.

______________________________________

*People Not Quite Like Us. Duh.

(12) Comments

Podcasting Richard Posner (and a banal thought or two about podcasting in general)

Virtually all of our readers already know that Glenn Reynolds and his lovely and talented co-host interviewed United States Circuit Judge Richard Posner on the subject of terrorism and its implications for the Constitution. Perhaps, however, you have not already listened to their podcast because you were waiting for my endorsement. If so, consider it endorsed. I have listened to perhaps six or eight editions of "The Glenn and Helen Show," and for my money this was the best of the lot. Click here for your choice of listening modalities, plus a round-up of links to related material.

The occasion for the interview is the publication of the prolific Judge Posner's most recent (and unbelievably timely) book, Not a Suicide Pact: The Constitution in a Time of National Emergency. If the podcast is any indication, it will shake the assumptions of armchair lawyers on both the left and right. I am ordering it today.

I have only just begun listening to podcasts in their best format, on an iPod. Indeed, I bought my first iPod (other than a Nano, which I had filled up with songs) two weeks ago for the precise purpose of listening to "The Glenn and Helen Show" and other podcasts while at the gym, hiking through the woods, and driving long distances. On Monday, the last full day of my Adirondack vacation, I walked nine miles over hill and dale taking in TGAHS and various other podcasty delights. I'll never look back.

The great thing about podcasting is its tremendous flexibility. Unlike interviews for a broadcast medium, a podcast can be of any practical length. That gives the interviewer great latitude to run with the conversation. In some cases, Glenn and Helen drive an interview conventionally. In others, multiple guests happily natter away and we, like Glenn and Helen, are basically along for the ride. The interview of Judge Posner was basically a series of extemporaneous lectures on various aspects of the intersection of civil rights and the fight against terrorism. Glenn and Helen let the judge just talk because, well, Judge Posner is so damned articulate that letting him talk was best move. Very few mainstream media hosts have that self control, probably because the "profession" of journalism demands that they intervene. In this regard, podcasting is exactly analogous to blogging -- neither are as constrained in their content or dimensions as their mainstream media counterparts.

Told you my thoughts were banal.

(0) Comments

Exelon/PSEG: A "mother of all cratered deals" update

Regular readers know that I occasionally declaim on things that amuse me in the business world, at least if they are at long remove from my industry. In that spirit, I have previously speculated that the long-pending merger between Exelon and New Jersey's Public Service Enteprise Group was in a lot of trouble. The New Jersey Board of Public Utilities has held up its approval of the deal in the hopes of securing a bigger basket of goodies for "the people of New Jersey," or at least specific people in New Jersey. The deal has now been hanging fire since December 2004, and in early August Exelon and PSEG served the BPU with an ultimatum. The BPU called the bluff, and Exelon and PSEG groveled for more time to sweeten the pot. All that is history is here, and, yes, I actually did write that the BPU has made Exelon's CEO "its bitch." Sorry, but we are talking about New Jersey public utility regulation.

Well, a month on it now looks as though the deal really is in serious trouble. Exelon has decided that it can no longer say that the deal is more likely to close than not, and accordingly has taken a massive charge to write off the transaction expenses that would have been capitalized (expensed over a period of many years) had it completed the deal. In doing this, Exelon's management is revealing that it is, frankly, tired. It says it will continue to labor on, but this charge is a more credible signal than the bluff in early August that the BPU had better hit the current bid or the deal will die.

I have no idea, by the way, whether the sale of PSEG "should" die from the perspective of New Jersey's "ratepayers". However, I have done enough acquisitions to know two things.

First, PSEG's management must be despondent. They have undoubtedly been running the company for more than a year around the assumption that it will be sold. It simply must be true that hundreds if not thousands of staff employees have left anticipating the loss of their jobs, or have been working as though they will soon lose their jobs (which is almost worse). The top team, which has been hanging on desperate for their severance packages, now will have to get back to the boring business of running an electric utility, and they will have to do it with a hollowed out and probably demoralized corporate staff.

Second, nobody else is going to try to buy Public Service Enteprise Group any time soon. As I wrote almost a month ago, who will buy PSEG knowing the BPU is going to demand more than $1.5 billion? Nobody. Which is why the price of a share of PSEG is down more than 4% this morning.

The only hope now is that some of those specific New Jersey people decide that half a loaf is better than none. Stay tuned.

(1) Comments

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Den Beste on "proportionality"

Mostly-retired blogging great Stephen den Beste lobbed in a guest post over at The Chicago Boyz on the matter of Israel's "disproportionate" response. I actually do not agree with den Beste's proposed answers to the questions "why did so many people demand 'proportionate' responses from Israel, and condemn Israel's bombing campaign as being 'disproportionate'?" However, in getting there he suggests a framework for thinking about modern war that is both powerful and instructive. For that alone it is well worth the two minutes it will take you to read it.

Via Glenn and our own K. Pablo.

(3) Comments

WiFi in Tupper Lake, New York

This post is a public service to people who find themselves in Tupper Lake, New York and Google "WiFi in Tupper Lake" hoping for information. If you are unlikely to be one of those happy few, move right along.

As far as I have been able to determine, there are two WiFi hotspots in Tupper Lake. One is at the public library on Lake Street, which has both public computers and free wireless internet access. Unfortunately, the library has pretty confined hours -- it isn't open on the weekend during the summer, when most visitors to Tupper Lake might want to take advantage of it. Fortunately, you can poach the signal by sitting on the bench just outside the front door. The last two summers I blogged from that bench just about every morning from roughly 6:30 to 8:30.

The better solution is the just-opened "Brick Oven Cafe," which is also on Lake Street, just across from the public library and the post office. The Brick Oven Cafe opens at 7 a.m. during the week (8 a.m. on Sunday), and it fills a heretofore unmet need in Franklin County, lattes and internet access under one roof. It has lots of space and lots of outlets for power, and there is no obvious reason why you couldn't decamp there and write the great American novel over the course of a summer. If you are in the area (perhaps to visit The Wild Center, which is, by the way, awesome), be sure to stop by.

(6) Comments

O'Quiz

The new O'Quiz is up! Vacation took an awful toll. I scored a mere 5 out of 10, just a hair's breadth more than the 4.24 average score.

(0) Comments

A September to remember?

Despite the impressive resurgence, the Hawkeyes now have to live down their September bugaboo, for it has been in the season's first month where the team has had its worst stumbles of late, pushing them out of even water cooler talk of title contention. In 2002, it was the infamous second half collapse in Kinnick Stadium against Iowa State and Seneca Wallace, after opening up a 24-7 lead no less, that was Iowa's only regular season loss. They would go on to sweep the Big Ten. In 2004 the Hawkeyes were crushed 41-7 at Arizona State after beating the same team 21-2 the year before at home. In 2005, the Hawks took it on the chin twice in September, first losing at Iowa State after quarterback Drew Tate was knocked out of the game in the first half, and then getting stubbed out like a cigarette butt at Ohio State, where Tate's return to the lineup made not one iota of difference.

This year, the Hawkeyes return what should be a pretty good football team. Drew Tate returns at QB, along with talented running back Albert Young and a strong offensive line. While the receiving corps is inexperienced, it has speed, and while they season Iowa can rely on three experienced tight ends, a position which has tended to be a prominent part of the Iowa attack. The kicking game looks characteristically strong, with return of Kyle Schlicher, one of the best kickers in the nation.

On the defensive side of the ball, the defensive line, a question going into last year, came into its own and looks like one of the best in the conference heading into the season. There were some key defensive losses, however, most notably the pair of all-everything 3-year starters at linebacker, Abdul Hodge and Chad Greenway, as well as cornerbacks who had both started nearly every game for the past four seasons. While there is talent filling in at both linebacker and cornerback, the lack of experience could mean some defensive problems early in the season.

Which brings us back to the dangers of September, which loom large. Iowa opens the season at home against I-AA Montana, but then must take its show on the road to the Carrier Dome to play Syracuse. The Orange were a big disappointment last year, but this is the kind of game that looks like trouble, at least based on recent Iowa history. On September 16th, Iowa hosts the always dangerous (to Iowa) Iowa State Cyclones, before taking a winnable road trip to Illinois. The Hawks will wrap up the perilous month at home against Ohio State, in a nationally televised night game on September 30th.

With two games on the road, and home games agains their biggest rival as well as the top ranked team in the country, September does indeed look rough for the Hawkeyes. The rest of the schedule is actually pretty accomodating, with the road game at Michigan in late October looming as the most dangerous matchup. And by October and November Ferentz usually has the Hawks playing at a very high level. The question is, can they defy recent history, gel early this year, and overcome the September challenge?

I certainly hope they do; a Hawkeye loss before the Ohio State game would have to be considered a pretty big upset. Ohio State, the top ranked team in the country, travels to Austin early on to try to avenge last season's loss to the national champion Longhorns. If the Buckeyes return with a win, and Iowa keeps its end of the bargain, that September 30th matchup in Kinnick could be a very special game indeed, with major potential ramifications. It has the makings of a September to remember in Iowa City.

(0) Comments

More on the characterization of the Hezbollah war

I will confess that I am more than a little bit bemused at the war going on within the ranks of the friends of Israel over which side "won" the recent round of fighting between Israel and Hezbollah. Regular readers know that the various authors of this blog generally agree that Israel improved its position at Hezbollah's expense, but we seem to be in the minority. Yes, we have the esteemed Edward Luttwak on our side, but that is cold comfort when you are arguing against Power Line, which leads a pack of conservative bloggers and other commentators who argue that Israel is in worse shape.

This is not the time to reprise all the arguments, but I did want to pass along Michael Young's interesting essay in Lebanon's The Daily Star, "The dilemmas of being an Iranian bullet." It was published five days ago -- an eternity in the blogosphere -- but as of this morning Technorati had tracked exactly no links to it, so it may be new to you. Young:

Hizbullah's efficient ward heelers are handing out cash, reportedly much of it Iranian, to persuade the party's Shiite supporters that the destruction of their homes and livelihood was worth it. However, a more pressing question is: At what point will Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, Hizbullah's secretary general, be forced into making an impossible choice where he must either reimburse his expanding debt to Iran or, by doing so, risk losing the backing of his own community? In other words, when will Hizbullah have to truly decide whether it is Iranian or Lebanese?

The question is ever more relevant in light of the ongoing tension between the international community and Iran over the latter's nuclear program. Iran had wagered on Hizbullah's missiles being a deterrent in the event of a conflict with the United States and Israel. That effect has been mostly lost thanks to the month-long Lebanon war. Hizbullah still has many rockets, and its infrastructure in the South is probably intact. But what it no longer has is a blank check from the Shiite population to pursue a new war of "honor" that will surely put most of them back in the streets again.

Amid the sanguine assertions of a Hizbullah victory, a colder assessment is needed to gauge just what the party achieved, or, rather, lost after July 12 - specifically what it lost Iran. Aside from Hizbullah's spent deterrence capability (only revivable at a high price) is the element of surprise when it comes to the party's training, tactics, and defenses. In the next war, the Israelis will come better prepared. The Lebanese Army is in the South, and a broader international force will probably soon deploy in the border area. That hardly makes a new war impossible, but were Hizbullah to take its weapons out of their containers to resume the fight, it would have to first confront the Lebanese state and the international community, meaning bearing a heavy responsibility for the aftermath.

Then there is the matter of Iranian calculations. If you were a Revolutionary Guards chief in Tehran, how would you view the latest conflict with Israel? You would doubtless marvel at Hizbullah's training (Iranian of course), but the ovation would end there. If it's true that hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent on arming and preparing the party, and that hundreds of millions, if not billions, more will be needed to rehabilitate Lebanon's Shiite community, then the Iranians got little for their outlays. The Lebanon war was useless to them, only making their nuclear program more vulnerable. That's one reason why Tehran organized military exercises before its formal answer on Tuesday to an international offer on ending uranium enrichment. The Iranians would have preferred to use Lebanon as a cushion to keep the conflict away from their borders; but Hizbullah torpedoed that by miscalculating the Israeli and American response to the July 12 abductions of two Israeli soldiers.

So now Nasrallah has a mounting debt owed the Iranians and little room to tell them that he cannot implement a request to heat Israel's northern border if the nuclear issue demands it....

What can Nasrallah do if Iran asks Hizbullah to resume military operations against Israel while Shiites are slowly rebuilding their lives? By refusing, Nasrallah could lose his sponsor and financier; by agreeing, he could lose his supporters.

Read it all.

Now, I agree that the result of the recent war was disappointing if measured against the expectation that Israel would pound Hezbollah into ash from which even a phoenix could not revive. Measured against a more realistic standard -- geopolitical progress against the last potent enemy on its border -- Israel may well have improved its position. At the least, we cannot know one way or another until the next step in the broader confrontation.

(7) Comments

Monday, August 28, 2006

"Attacked by the bacteria of stupidity"

Ghazi Hamad, spokesman for the Hamas-controlled Palestinian Authority government and a former newspaper editor, has gone stark, raving, er, sane:

Dismissing Israel's responsibility for the growing state of anarchy and lawlessness in the Gaza Strip, Hamad said it was time for the Palestinians to embark on a soul-searching process to see where they erred.

"We're always afraid to talk about our mistakes," he added. "We're used to blaming our mistakes on others. What is the relationship between the chaos, anarchy, lawlessness, indiscriminate murders, theft of land, family rivalries, transgression on public lands and unorganized traffic and the occupation? We are still trapped by the mentality of conspiracy theories - one that has limited our capability to think."

Hamad admitted that the Palestinians have failed in developing the Gaza Strip following the Israeli withdrawal and in imposing law and order. He said about 500 Palestinians have been killed and 3,000 wounded since the Israeli pullout, in addition to the destruction of much of the infrastructure in the area.

By comparison, he said, only three or four Israelis have been killed by the rockets fired from the Gaza Strip over the same period.

"Some will argue that it's not a matter of profit or loss, but that this has an accumulating effect" he said. "This may be true. But isn't there a possibility of decreasing the number of casualties and increasing our gains by using our brains and making the proper calculations away from demagogic statements?"

The Hamas official said that while his government was unable to change the situation, the opposition was sitting on the side and watching and PA President Mahmoud Abbas was as weak as ever.

"We have all been attacked by the bacteria of stupidity," he remarked. "We have lost our sense of direction and we don't know where we're headed."

Addressing the various armed groups in the Gaza Strip, Hamad concluded: "Please have mercy on Gaza. Have mercy on us from your demagogy, chaos, guns, thugs, infighting. Let Gaza breathe a bit. Let it live."

Governing isn't all it's cracked up to be, is it Mr. Hamad?

(5) Comments

Moqtada al-Sadr and the bounty on "concubines"

Fouad Ajami's book on Iraq, The Foreigner's Gift: The Americans, the Arabs, and the Iraqis in Iraq, is a long historical essay on the subtle interplay between the huge number of factions that have been struggling for ascendency in Iraq since the fall of Baghdad. Ajami has been to Iraq six times in the last three years, and fills his book with vivid, almost lyrical descriptions of events that are shaping the new Iraq, including many that have not been reported by wire services, or at least cannot be understood through wire service stories. This short passage out of many pages devoted to Moqtada al-Sadr's movement (of which there will be more in my "official" review of Ajami's book) struck me as particularly revealing of the brutality of his brand of radicalism, and its strange similarity to bin Ladenism, at least as practiced in the Iraq war:

The Mahdi Army was a movement of the dispossessed; order and hierarchy and property, and the rule of the elders and the tribal notables arrayed around the senior jurists, now sought to contest the ways of the street. Sadr and his lieutenants has grown increasingly radical and unsettled. In the city of Basra, on the very same day that Sheikh Qabanji had taken on the Sadrists, a representative of Moqtada al-Sadr, Sheikh Abdul Sattar Bahadali, speaking to three thousand worshippers, with his assault rifle next to him, offered a reward of a hundred thousand Iraqi dinars (seventy dollars) to any believer who would capture a British female soldier; he said that soldier could then be kept as a concubine of her captor. There was no need for the clerical hierarchy to speak of the dangers posed by the Sadrists. The latter were doing a fair job of it themselves. Anti-Americanism, an animus toward the Anglo-American coalitoin, was one thing, but the keeping of "concubines" and slave women was a wholly different matter, a clear pathology on display.

There was no subtlety here: this was a direct appeal by Sadr and his inner circle to the yearnings of the young and to their notinos of hegemony and war booty. This primitivism, it so happened, came on the very day that an audiotape of Osama bin Laden turned up offering "ten thousand grams of gold" to anyone who would kill Paul Bremer or the Algerian-born United Nations envoy to Iraq, Lakhdar Brahimi, and "one thousand grams of gold" to anyone who would kill a civilian or a soldier from Japan or Italy. The air was filled with talk of "infidels" and "apostasy" and "Crusaders" and "slave women" and "grams of gold." Sistani's gift remained the assurance given a people caught in the throes of great upheaval that their tradition was there for them as a safe harbor, that amid the troubles there remained political limits and reason. Men can't live on their nerves, and Sadr had nothing to offer save ceaseless agitation. Tyranny had wrecked the country; now anarchy offered ruin in its own way.

When the settled histories of the Iraq war are finally written a generation from now, it will be interesting to see whether future historians regard the decision not to arrest al-Sadr early in the game as one of the great errors of the American regency.

(6) Comments

A question for our readers: What will the 9/11 generation accomplish?

If you've read my most recent post, you know I am thinking about generations this morning. It is perhaps sloppy history to characterize generations of Americans, but we do it anyway. The misleadingly named "greatest generation" that fought World War II, for example, became the only decidedly statist generation in American history. It grew up believing that the New Deal rescued the United States from the Depression, and the waging of World War II stands as perhaps the single greatest accomplishment of our federal government. The result is that the generation born between roughly 1910 and 1930 had a great belief in state action that influenced American politics well into the 1980s.

Similarly, the generation that came of age during the Vietnam war is today at the peak of its power. The political fortunes and attitudes of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, John Kerry, John McCain, Al Gore and any number of others have been influenced by their relationship with the Vietnam war. The Vietnam war was in some respects the central historical backdrop to the presidential election of 2004. Obsession with Vietnam has colored -- some would say warped -- the prosecution of and opposition to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. We do not yet have a nuanced understanding of the impact of Vietnam on the American political and geopolitical landscape, but we can be sure that the influence of that war has been pervasive, far beyond its direct consequences.

So what will be the impact of the generation that has come of age during the last five years? More than 300,000 young Americans have served in Afghanistan and Iraq, and many of them will come home and eventually enter careers in government, journalism, business, academia and politics. There are many more Americans who did not fight in those wars, who know virtually nobody who has, and who know what they think they know from abstract media -- press accounts, books, photographs and fauxtographs, and blogs of the right and left. What effect will these two groups have when they become the leaders of our government, economy and culture? If you answer in the comments -- and I very much hope you do -- consider particularly the likely impact of this generation on American foreign policy. What will these returning veterans teach us about the Arab and Muslim world, and how will the cohort that stayed at home react to that instruction?

Fire at will.

(10) Comments

Our system, or Sweden's?

Tim Worstall is devestating in his comparison of income, income distribution and standard of living in the United States and various European paradises, including Sweden.

One of the joys of my working life is that I get to read papers like "The State of Working America" from the Economic Policy Institute. They are, as you may know, the people who urge that the USA become more like the European countries, most especially the Scandinavian ones. Less income inequality, more leisure time, stronger unions and so on. All good stuff from a particular type of liberal and progressive mindset -- i.e. that society must be managed to produce the outcome that technocrats believe society really desires, rather than an outcome the actual members of society prove they desire by building it.

I will admit that I do find it odd the way that only certain parts of the, say, Swedish, "miracle" are held up as ideas for us to copy. Wouldn't it be interesting if we were urged to adopt some other Swedish policies? Abolish inheritance tax (Sweden doesn't have one), have a pure voucher scheme to pay for the education system (as Sweden does), do not have a national minimum wage (as Sweden does not) and most certainly do not run the health system as a national monolith (as Sweden again does not). But then those policies don't accord with the liberal and progressive ideas in the USA so perhaps their being glossed over is understandable, eh?

From there, Worstall looks at the results of these two systems. He demonstrates rather convincingly (to a non-economist, at least) that the poor in the United States earn or receive approximately the same percentage of the median United States income as the poor in the more socialist countries of Western Europe. The biggest difference between the two systems is that the American economy is growing faster, and the top 10% in the United States is substantially wealthier than in other countries. This leads us to two questions Worstall does not answer.

First, if our poorest 10% are doing about as well as their counterparts abroad and the richest 10% are doing much better, does that mean that the 80% of Americans who are at neither extreme are doing slightly less well than their foreign counterparts? I admit that I do not have the energy to dig beyond Worstall's column to the linked references to see if the answer is in there somewhere.

Second, is the greater wealth of the top 10% in the United States in and of itself troubling? That is a normative question, and it drives most of the emotion around the politics of "distributive justice," or "envy," depending on your point of view. Perhaps because I am blessed to occupy the upper tenth, I do not think that wealth at the top is inherently problematic, at least if the poor are taken care of (which they are, if Worstall is right). Unlike the rich of days gone by, America's wealthy are -- more than any society in the history of the human race -- an aristocracy of merit. Most people, if they avoid catastrophic personal decisions (debilitating vices, pregnancy out of wedlock, divorce, or profligacy), can make a pretty good life for themselves in the United States. If a family puts together consecutive generations of had work and no vice, it has a great chance of moving into the upper bracket, at least temporarily. But screw-ups are costly at virtually every level of income. Even many of the "rich" in the top 10% are but one or two generations away from the middle class or worse, and an extraordinary number of their children or grandchildren will produce so little compared to their consumption that they will fall out of the top band. If you are in the upper middle class or know a lot of people who are, you also know that plenty of them have one or more children who will not be economically successful in their own right. Even if those children get by on money from their parents, the old fortune almost never lasts beyond another generation. Except for a miniscule number of the mega-rich, Americans can only "coast" for about one generation. After that, somebody needs to produce more wealth than he or she consumes or the family will drop into the middle class or below. That is the American system's great discipline.

MORE: I often think the trick to happiness and success in the United States is to think in terms longer than a generation. If you work only for yourself or your own generation, you have a small chance of becoming rich and will naturally envy those that have. You will squander the wealth that your parents earned, and spend whatever you make in the false belief that owning more things will bring more happiness. It is far more satisfying to thinking of yourself as making a contribution to the long-term success of your family. If you believe it is your job to preserve the wealth that was created by your parents and -- in some fortunate cases -- grandparents, and to endow your children with the values and financial options that will allow them to produce more than they consume, your family can be successful at many different endeavors for many generations. And you don't need to have children to gain happiness from thinking in generational terms. Charlottesvillain, Greenman Tim and I had a great aunt who never married, but who was able to pass along both financial support -- she was one of the first female securities analysts on Wall Street, having originally been a librarian -- and the extraordinary example of her love and life to her many nieces and nephews and descendents thereof. She has contributed as much to the success of her "descendents" as most people who actually have children, and was extremely happy for having done so.

Horatio Alger still lives in America. The myth -- which we should disabuse early and often -- is that success is the work of just one generation. It rarely is.

CWCID: Glenn Reynolds.

(15) Comments

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Hezbollah admits a catastrophic intelligence failure

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah said today that he did not expect his attack on Israel to lead to war:

Hezbollah leader Sheik Hassan Nasrallah said in a TV interview aired Sunday that he would not have ordered the capture of two Israeli soldiers if he had known it would lead to such a war.

Guerrillas from the Islamic militant group killed three Israeli soldiers and seized two more in a cross-border raid July 12, which sparked 34 days of fighting that ended with a cease-fire on Aug. 14.

"We did not think, even 1 percent, that the capture would lead to a war at this time and of this magnitude. You ask me, if I had known on July 11 ... that the operation would lead to such a war, would I do it? I say no, absolutely not," he said in an interview with Lebanon's New TV station.

This is not the first time a Hezbollah officer has claimed to have misjudged the Israeli reaction, although if Nasrallah has said as much before today I must have missed it. The more interesting question, from the perspective of a Westerner, is why he would say such a thing even if it were true? In this one statement, Nasrallah has admitted that he does not understand the enemy he has vowed to destroy, and that he is willing to risk massive destruction in Lebanon notwithstanding his ignorance. Is he not admitting an intelligence and managerial failure of the first order? Why would any Lebanese reading this confession trust Nasrallah to provide security? Has he not revealed himself to be incompetent at the very thing that he relies upon for his legitimacy?

Perhaps the worst part of Nasrallah's claim -- at least from the perspective of the average Lebanese -- is that he is in effect telling Israel that he cannot be deterred. If, after all, he completely misjudges the preparations and threats of his enemy, how can Israel presume that Nasrallah will react rationally to future threats to retaliate? If Israel cannot, in fact, rely on Nasrallah's ultimate rationality, then Israel must strike Hezbollah massively and preemptively. To do anything less would be folly.

Now, I am sure that Nasrallah thinks that in making this point he is scoring a propaganda point over Israel: "Look at what barbarians the Jews are -- nobody would have expected such a massive response!" Many people, including perhaps most journalists, academics and Europeans, will be taken in by this. But anybody who takes Nasrallah at his word has to be worried that Hezbollah's high command launched a war by mistake. The obvious implications for the region, and particularly Lebanon, are so scary that it is very strange that Nasrallah would admit this, even if he thinks it will make Israel look bad. It certainly doesn't make Hezbollah look good.

(8) Comments

White guilt and Islamic rage

Shelby Steele has written the article to read this morning:

White guilt in the West--especially in Europe and on the American left--confuses all this by seeing Islamic extremism as a response to oppression. The West is so terrified of being charged with its old sins of racism, imperialism and colonialism that it makes oppression an automatic prism on the non-Western world, a politeness. But Islamic extremists don't hate the West because they are oppressed by it. They hate it precisely because the end of oppression and colonialism--not their continuance--forced the Muslim world to compete with the West. Less oppression, not more, opened this world to the sense of defeat that turned into extremism.

But the international left is in its own contest with American exceptionalism. It keeps charging Israel and America with oppression hoping to mute American power. And this works in today's world because the oppression script is so familiar and because American power cringes when labeled with sins of the white Western past. Yet whenever the left does this, it makes room for extremism by lending legitimacy to its claim of oppression. And Israel can never use its military fire power without being labeled an oppressor--which brings legitimacy to the enemies she fights. Israel roars; much of Europe supports Hezbollah.

Over and over, white guilt turns the disparity in development between Israel and her neighbors into a case of Western bigotry. This despite the fact that Islamic extremism is the most explicit and dangerous expression of human bigotry since the Nazi era. Israel's historical contradiction, her torture, is to be a Western nation whose efforts to survive trap her in the moral mazes of white guilt. Its national defense will forever be white aggression.

The bolded sentence defines the difference between the "anti-war" advocates who believe that the United States can end this war unilaterally, by altering its policies, and those of us who believe that we will have to fight this enemy, this insurgency within the Muslim world, until its ideology is discredited and it cannot fight on. If you accept the premise that competition with and attraction to the West drives much more Arab anger than oppression by the West, do you believe that the economic, civic, political and military failure of the Muslim world, particularly the Arab Muslim world, is primarily a function of Western coercion, or poor decisions Muslims have made themselves?

(3) Comments

Saturday, August 26, 2006

What if they had blown up the jets?

Niall Ferguson imagines what would have happened had the jihadis blown up those aircraft flying from England to America. It would have been a disaster, in no small part because of the likely very different reactions in Britain and the United States.

(3) Comments

Annals of Bush multilateralism: China nudges the oil tap

On Thursday we passed along the news that U.S. Treasury officials had persuaded Vietnam to deny banking services to North Korea. The stated reason was to cut off North Korean counterfeiting and money laundering, but (speculation alert) the real reason was to make it very difficult for North Korea to get paid for anything -- including particularly technology transfers -- without the United States knowing about it.

Today we read that China has been cutting back on the oil that it delivers to North Korea:

China, the communist North's closest ally and key provider of oil, has agreed with South Korea to cooperate to prevent a possible North Korean nuclear test.

China also has reduced "a significant amount" of its oil supplies to Pyongyang since the July 5 missile launches, South Korea's Chosun Ilbo newspaper said.

The report cited unnamed officials at an oil storage terminal near the Chinese border city of Dandong.

The problem with the Kerry strategy of unilateral engagement with North Korea is that we actually have far fewer cards to play than either China or South Korea. Any solution that those countries do not "own" is doomed to fail, just as the much-heralded Clinton administration agreement failed. We should not do either country the favor of making North Korea first and foremost an American problem, both because that is what Kim wants us to do (which ought to be reason enough to deny it) and because it lets China and South Korea get away without fashioning their own solution.

(5) Comments

Iran: Two routes to a bomb

Iran announced today that it has opened its 40 megawatt heavy-water reactor. I confess that I am no expert in nuclear technology, and do not even know enough at a pop level to write without grave risk of error. However, I can quote from a previous post, which was essentially my notes from a "roundtable discussion" on Iran at Princeton University at the end of March.

Professor von Hippel gave an interesting technical presentation about Iran's nuclear options, the sum and substance of which is that they are building their power program specifically around "dual use" technologies for which there are alternatives. If their sole concern was to build a power system, they could do so in ways that are much less inflammatory.

"It's a tale of two isotopes, and two routes to the bomb." U-235 will sustain a fission chain reaction if separated, and U-238 if turned into plutonium. Iran is pursuing both methods.

Iran is furthest along in separating out U-235 using gas centrifuges. You fill a spinning cylinder with a gaseous uranium. The heavier molecules go closer to the wall of the centrifuge, and a scoop skims them off. For a power reactor, you need a 4% concentration, but for weapons you need a 90% concentration. A cascade for power generation requires 987 centrifuges to get to 4% concentration, and a weapons grade cascade rquires around 4000 centrifuges (see, for example, a captured Libyan design). Professor von Hippel showed a slide of first-generation Urenco centrifuges in the Netherlands in the 1970s, a vast room that appeared larger than an airplane hanger with thousands of the things, all spinning down U-235.

Iran has build underground centrifuge halls, suitable for housing 50,000 of them. Professor von Hippel displayed a satellite image of the Natanz facility, which revealed the constructon of two larged centrifuge halls, plus a pilot plant for perfecting the technique. You can see a copy of the satellite image here.

What could Iran do with the 1000 centrifuges in the pilot plant?Master the technology for commercial-scale enrichment.

Make enough weapon-grade uranium for a bomb in one year using natural-uranium feed.

Produce low-enriched uranium for a year and then enrich the product to enough for a bomb in two months.

Iran could also try to build a clandestine enrichment plant.

No one has argued that Iran could produce enough HEU for a single nuclear weapon before 2009. (emphasis in original slide)

There is also the plutonium route -- India's chosen path, for example, and Israel's. Iran is building a 40 megawatt plant, which could produce enough inventory for a couple of Nagasaki-sized bombs a year.

Iran is pursuing two tracks in the development of is nuclear program, both of which could lead to a nuclear weapon, and both of which have alternative routes that are less provocative. If I understood Professor von Hippel correctly, we thought in March that the U235 strategy -- requiring centrifuges -- was further along than the heavy water reactor strategy. Does today's news reveal the judgement of March to have been incorrect? If you know more than I do, which is likely, offer your thoughts and links in the comments to this post.

Thoughtful dovish observers obviously do not believe that the case has been made that Iran is in fact developing a nuclear weapon, but that misses the point. Whether or not Iran is actually developing a weapon, it can choose to make the world nervous or comfortable on a question of staggering geopolitical moment. It has consciously chosen to make the world nervous because it is hoping to exploit the ambiguity for advantage. Whatever the reality of Iran's weapons program, there is no question that it is trying to gain the advantage of having one. The West needs a strategy to deny Iran that advantage, whether or not it finds sufficient evidence of a weapons program to launch a preemptive war. Iran needs to be punished not for having a nuclear program per se, but for intentionally promoting the insecurity of other countries. Indeed, if Iran never did that, nobody would much worry that it was developing a bomb.

(4) Comments

Morning raft

Cratology

I admit, I'd be more likely to go

China may be giving striptease funerals the last rites after officials arrested five people and ordered an end to the practise, state media said.

Strip shows have been commonly used to attract more mourners to funerals, as villagers believe a crowded send-off brings more honor to the deceased, Xinhua news agency said.

Folks, this is what happens in a police state. They ban strip-tease funerals, and then turn neighbor against neighbor in their zeal to stamp it out:

After the television report, the local government quickly issued an order to stop the practice and demanded that village committees have to report details of each funeral plan within 12 hours after a villager dies.

A hotline was also set up for residents to report on "funeral misdeeds," it said.

How long will it be before a Chinese strip-tease funeral is worked into a Ben Stiller comedy?

(0) Comments

Reviewing Never Quit The Fight: A long drink from the firehose

Reading Ralph Peters is like drinking from a firehose. He hammers away with the toughest, most confrontational prose of any regular newspaper columnist that I know of, and reading hundreds of pages of Peters over a few days requires more than the usual emotional energy. Still, Ralph Peters is our most original analyst of military affairs writing for a popular audience, and there is vastly more to be gained from reading the eighty or so of his columns and longer articles in Never Quit The Fight than, say, the corresponding output of any columnist of The New York Times.

Peters examines military affairs and geopolitics through the prism of history and from the perspective of a soldier. Through all his work there is nothing but respect for the American soldier, nuanced contempt for the Pentagon brass, unreconstructed scorn for Donald Rumsfeld and his staff, condemnation for America's enemies, and the relentless application of historical perspective to America's present war and geopolitical opportunities. While most Democrats would dislike Peters for his often repeated belief that our enemies must be beaten so badly and unambiguously that they lose the will to fight, Peters is no partisan. He has clear political opinions, but is extremely critical of both Republicans and Democrats. From the first page: "A national election offered the American people one of the poorest choices in our history, between an incumbent administration that stood for arrogance, corruption, and security, and a challenger who emanated fecklessness, weakness, and a spirit of surrender." No arguing with that, I'm afraid.

Peters sharpest observations turn on the relationship between weapons procurement and America's likely warfighting requirements. In short, he believes that the defense industry, the Pentagon brass, and the Congress have, through a combination of stupidity and self interest, seduced the rest of us into believing that small numbers of extraordinarily expensive and technologically advanced weapons systems can both achieve American military objectives and substitute for quantity. Peters believes that these weapons will not achieve our military objectives for two main reasons. First, they derive from a misapprehension of the purpose of war:

Precise weapons unquestionably have value, but they are expensive and do not cause adequate destruction to impress a hardened enemy. The first time a guided bomb hits the deputy's desk, it will get his chief's attention, but if precision weaponry fails both to annihilate the enemy's leadership and to somehow convince the army and population it has been defeated, it leave the job to the soldier once again. Those who live in the technological clouds simply do not grasp the importance of graphic, extensive destruction in convincing an opponent of his defeat.

In this passage there is a taste of one of Peters' collateral themes: that the purpose of war is to make your enemy submit, and that most enemies will not submit until both their army and their population has been beaten so severely that they have lost the will to resist. Precise targeting allows for much reduced destructive power, which results in much reduced destruction. Yes, we no longer flatten cities to destroy an enemy's industrial base; we drop a JDAM through the ventilation shaft of a specific factory and spare the non-military buildings and people which in earlier wars would have also been destroyed. The result is that we no longer truly defeat our enemies, not to the extent required to ensure we will not have to fight them again.

Second, extravagant weapons systems run a serious risk of failing the specific missions for which they are deployed. These mission-specific failures are of at least two kinds. One is that we may find ourselves overwhelmed by enemies who deploy cheaper systems in great quantity. This broadside attack against the Air Force is typical Peters:

America needs a strong Air Force, but we have the wrong Air Force. The service's leadership, military and civilian, displays greater loyalty to the defense industry than to our national defense (the contractors who supply the Air Force teem with retired generals). Today's Air Force clings to a fight-the-Soviets (or at least the Chinese) model with greater passion than yesteryear's Army clung to the horse cavalry.

And Air Force leaders lie. Last year [2004], in war games with the Indian air force, our blue-suiters suffered embarrassing defeats. Our guys were arrogant and failed to think innovatively. We also had crucial high-tech gear turned off. The Indians used imaginative tactics -- and overwhelmed us with numbers.

Our Air Force's response? To insist the humiliation "proved" the need for the [three-hundred-million-dollar-per-copy] F/A-22. Yet purchasing that gold-plated piece of junk means that we could afford still fewer aircraft in the future -- we could be swarmed by other countries with lower-tech, affordable planes, just as the Indians did it.

Quantity matters, but also design. In a December 2005 article in Armed Forces Journal, Peters believes that the Navy's fetish for "grand fleet action" is preparing us for a war we are unlikely to fight:

As a former Army officer and a recent convert to the belief in the primacy of naval power, it appears to me that our Navy will have three overarching requirements in the future, only one of which has much appeal to sea-service officers. In order of importance, those demands are:

1 The ability to protect our maritime trade while interdicting that of an enemy; policing the sea lanes under the conditions of peace or lesser crises and dominating them through unrestrained power and strategic blockades in wartime.

2 The ability to promptly destroy or otherwise neutralize the naval capabilities of any enemy power or combination of hostile powers.

3 The ability to influence land warfare through massive firepower delivered anywhere on the globe, no matter the distance of the target from the sea.

At present, our Navy remains fully serious only about the second requirement, while the strategic issues of the moment make the third particularly appealing to those outside the Navy and to those within the service who are anxious, above all, to preserve funding. Yet, the decisive capability in a future great war would be the first requirement, with the second mission most useful in support of the broader control of the seas and the third an adjunct (if a critical one) to the operations of the other services.

While stressing again that a war with China is neither inevitable nor desirable, consider alternative historical analogies for how such a war might be waged and, ultimately, won.

First, the grand fleet action so appealing to those who command warships would be unlikely to resemble Midway or even the final naval battles fought as our forces neared Japan. A naval exchange with China, fought in strategic proximity to the Chinese mainland, would probably result in a second Jutland, a far more lethal and more dispersed exchange in which the Chinese, after inflicting more damage on our Navy than we allow in our war games, would nonetheless realize that the cost of doing so was prohibitive to their own force. The remaining Chinese fleet-in-being would become a fleet-in-hiding, bottled up and wary of further encounters.

The crucial naval activity in defeating China would be a rigorous, globe-spanning blockade that sweeps aside peacetime civilities and prevents China from receiving any resupply of raw materials, especially oil and gas. (A crucial indicator that the Chinese anticipate a war would be an attempt to accumulate massive, dispersed stockpiles of vital resources.) As China's appetite increases, it will become ever easier to bring its economy to its knees by closing the sea lanes (and freezing its global accounts and investments, by any means necessary). Pipelines, no matter how ambitiously constructed, not only could not provide adequate supplies, but — as U.S. forces learned to their dismay in Iraq — are easy to interdict.

A war with China would be a long war (even with resort to weapons of mass destruction), involving the sort of blockade that starved Germany in the First World War, combined with a strategic pummeling of China's vulnerable industrial base and its military. Just as Iraq is a boots-on-the-ground war, a war with Beijing would be a destruction-from-a-distance war, waged in the hope that internal rivalries in China would lead to the profound sort of regime change we saw in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1917. (Internally, China is becoming more unstable, not less so). Our grand strategy in such a conflict would be to turn the conflict inward, making it a Chinese-versus-Chinese struggle.

On the high seas, the role model for our naval captains would be less Bull Halsey and more Raphael Semmes — skipper of the Confederate cruiser Alabama, the greatest commerce raider of the Civil War. While it is hard today to imagine our vessels taking hundreds of merchantmen into custody — or sinking them — the issue of maritime trade will shape our naval future. In a globe-spanning war, shipping can only proceed at our sufferance. Faced with a war about our continued pre-eminence and even survival — enduring asymmetric Chinese attacks on our homeland — we will do what needs to be done, without regard for the niceties of international law or custom....

In this age of distinctly unpeaceful peace, our Navy is apt to find itself tasked to behave far more intrusively with foreign shipping and local maritime craft than would presently be comfortable to our National Command Authority, Congress or the Navy itself. Practical requirements, forced upon us by hostile actors, will dictate policy (despite Sept. 11, we still are not remotely serious about warfare). Policing the high seas is going to demand a Navy with more, if often smaller, vessels as the service reluctantly assumes the role of civilization's global coast guard.

A worrisome trend in our Navy is the elevation of technology above personnel to a degree never seen before. It appears to an outside observer that the desire to reduce crew size to a minimum on the next generation of vessels may prove to be a prescription for sharply reduced capabilities, if not occasional disasters. Despite the notion that a warship might seal itself against an assault, a crew so small that it cannot defend itself will, sooner or later, find itself in a position where it cannot defend itself. Postmodern manning initiatives appear to allow for no vital redundancy. Yet, management theories and personnel-cost savings that sound awfully good at budget time in the Navy Annex simply replicate the false savings the Army garnered by reducing manning so severely that deploying units had to be augmented by raiding the personnel rosters of like units (or the Reserve component).

Warfare remains an endeavor of the people, by the people and for the people. The machines are means, not ends. While there is an obvious cultural divide between the Navy and Air Force, in which people support systems, and the Army and Marines, in which systems support people, the Navy must overcome its utterly false belief that all problems have technological solutions. People matter.

Peters is unambiguous: We are not building the ships we will need to fight the most probable next war. Why? Because no defense contractor or admiral wants to build a zillion small, cheap ships that can house a few Marines and interdict the Chinese merchant marine.

Beyond his critique of the American military at peace and at war, Peters is an enormously creative thinker geopolitically. He sees far more potential in Africa, particularly South Africa, than most Western observers, and he thinks that we are squandering an opportunity to build strong alliances with the key powers in Latin America. Indeed, Peters believes that the two big southern continents will be so important that the twenty-first century will also be an "Atlantic" century, only this time centered on the south Atlantic. I am not sure he's correct in the grandiosity of his vision, but he's probably right about the basic direction.

Without ever devoting a column or essay particularly to the topic, Peters thinks more deeply about the degree to which humans are wired for faith than most journalists. Peters is not obviously devout in any one denomination -- he snarks on the Christian right with as much intensity as a blue state university professor -- but he believes that the Western chattering classes simply do not understand the crucial importance of faith to the motivation of human beings. Few other synidicated columnists would write these paragraphs, for example:

If we are serious about understanding our present -- and future -- enemies, we will have to rid ourselves of both the plague of political correctness (a bipartisan disease so insidious its victims may not recognize the infection debilitating them) and the failed cult of rationalism as the only permissible analytical tool for understanding human affairs. We will need to shift our focus from the individual to the collective and ask forbidden questions, from inquiring about the deeper nature of humankind (which appears to have little to do with our obsession with the individual) to the biological purpose of religion.

The latter issue demands that we set aside our personal beliefs -- a very tall order -- and attempt to grasp three things: why human beings appear to be hardwired for faith; the circumstances under which faiths inevitably turn violent; and the functions of religion in a Darwinian system of human ecology.

The answers we are likely to get will satisfy neither secular commissars nor their religious counterparts, neither scientists schooled to the last century's reductionist thinking nor those who insist on teaching our children that the bogeyman made the dinosaurs. We are at the dawn of a new and deadly age in which entire civilizations are threatneed by the dominance of others. They are going to default to collective survival strategies that will transform their individual members into nonautonomous parts of a whole. We are going to find that, after all, we may not be masters of our individual wills, that far greater forces are at work than those the modern age insisted determined the contours of our lives. Those greater forces may be god or biology -- or a combination of the two -- but they are going to have a strategic impact that dwarfs the rational factors on which our faltering thinking still relies.

Applied to human affairs, rationalist thought too easily becomes just another superstition. Even the unbelievers among us are engaged in a religious war.

One might add, although Peters did not, that George W. Bush understands at least this last point. With the possible exception of Hillary Clinton and a senator recently drummed out of the party, who among Democrats can say the same?

I certainly do not agree with Peters on every point, but I learn something on almost every page. Left or right, Ralph Peters makes you think hard about your conception of the world. If you read Peters columns in the New York Post, you know what I'm talking about. If you don't, start by reading Never Quit The Fight.

(10) Comments

Friday, August 25, 2006

Islam's trajectory

I claim no expertise in matters of religious history, and have no genuinely considered opinion as to whether the hideous crimes carried out in the name of Islam are inherent to the religion or the product of its perversion. Christian churches have certainly also committed great crimes that today we believe to have been wholly inconsistent with the teachings of Christ, so I am open to the claim that Islam is not practiced in accordance with the true teachings of the Prophet.

With that disclaimer, I commend to you David Forte's interesting essay, "Islam's trajectory." Forte argues that many of the things that Westerners most dislike about Islam -- its persecution of apostates and its treatment of women and minorities -- is the product of the reconstruction of the religion to fit Arabian tribal politics and the requirements of empire. If I understand Forte correctly, the point is not to defend Islam from its critics so much as to observe that there is plenty of liturgical history on which to base a moderating reformation (if, in fact, any call to moderation can at the same time be sufficiently zealous to change 1300 years of religious and cultural tradition).

The essay is long, so if you aren't on vacation print it off and read it the next time you are stuck at some airport.

(18) Comments

The fraudulent victory

Regular readers know that we have consistently rejected the meme that Hezbollah won a victory in the recently suspended fighting. Well, if Amir Taheri is to be believed, the Shia of Lebanon don't think they won, either.

(5) Comments

Feminists, the oppression of women under Islam, and old allies

Glenn Reynolds linked to a very interesting essay by a left-wing Australian feminist who wonders why so many of her sisters in the movement not only refuse to condemn Islamist extremism, but walk in solidarity with it:

In Tehran in June, several thousand people held a peaceful demonstration calling for legal changes that would give a woman's testimony in court equal value to a man's. The demonstrators, most of them women, were attacked with tear gas and beaten with batons by men and women from Iran's State Security Forces, according to Amnesty International. Iranian women may not travel without their husband's permission but they are allowed to wield a truncheon against other women.

Do you think women in Western countries marched in solidarity with the Iranian women demonstrators? Of course not. Do you think there are posters and graffiti at universities condemning the Iranian President? Of course not. You know, without needing to go there, that any graffiti at universities will be condemning George W. Bush, not Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. (I concede Bush is easier to spell.)

You know, before you get there, that at the Melbourne Writers Festival starting this weekend the principal hate figures are going to be Bush and John Howard. You know there will be many sympathetic references to David Hicks but probably none to Ashraf Kolhari, an Iranian mother of four who has been in jail for five years for allegedly having sex outside marriage and, until last week, who was under sentence of death by stoning.

Thank goddess, as they used to say: a few Western feminists have begun to wonder why women who once marched for women's rights are marching alongside people who would take away even the most basic of those rights.

The latest is Sarah Baxter, a former Greenham Common protester, who in Britain's The Sunday Times had this to say about a recent demonstration in London calling for a ceasefire in Lebanon: "Women pushing their children in buggies bearing the familiar symbol of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament marched alongside banners proclaiming 'We are all Hezbollah now', and Muslim extremists chanting, 'Oh Jew, the army of Mohammed will return'.

The author goes on to speculate as to the reason for the perverse willingness of feminists to support political movements that would stone women, but not men, for having sex out of wedlock: