Sunday, September 23, 2007

One for the Iowans

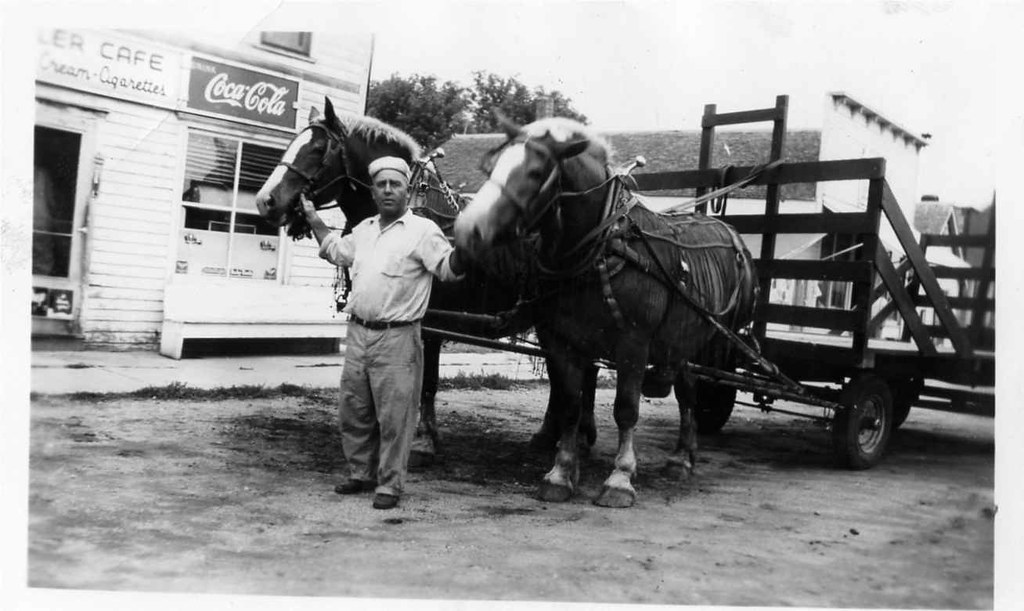

A friend of mine with deep roots in the Hawkeye State, inspired by my link to Iowahawk's "machine shop of horrors" post (pictures of old time farm tools), sent me an interesting old photograph of threshing time in the Iowa of the 1920s. His email is below the picture:

Around Iowa, there were threshing "teams," which were basically just a bunch of neighbors who agreed to harvest each others crops and to engage in the then manual process of removing the corn from the cobs once the corn was brought in from the field. (This is now all done in the field by huge combines that pull the corn off the stalk and then remove the kernels from the cob, all in one fell swoop.) You can imagine how much time that would take if you did it by hand, so there was real benefit in pooling resources, especially since there was a clear need to get the crops out of the field as soon as possible once it was ready and to then get the corn in a form you could use.

Threshing day was apparently a big event. My mother says you would skip school and, of course, you had to prepare enough food for everyone to eat. The remarkable part to me is that my grandfather farmed the very same 160 acre plot of land from when he got married right after World War One through the late 1960's. The critical difference, however, was equipment. Before World War Two, it was all horses. [A picture of his team appears at the end of the post. - ed.] After World War Two, however, everyone got tractors and combines, and it was all automated. It was clear to me as a kid that farming 160 acres with a team of horses would have been a huge task and about as much land as could be farmed by one person (and even then, you had to pool resources to do it). Once the tractors showed up though, everything changed. Farming 160 was not all that difficult, and the more industrious farmers were able to farm 320 or even more acres. Now, the guys who farm our farm (five brothers around our age) farm over 5000 acres and use equipment that looks like it should be used for a lunar landing and costs about the same. What is less clear to me, however, is whether the quality of life has really improved for anyone other than the implement dealers. You could easily feed your family and make a good living on 160 acres back in the pre-tractor era. Today, there is no way you could do that.

That Iowa farmers today can cover thirty times the acreage at higher levels of productivity than in the 1920s is not surprising, and it explains why Iowa's population today is far smaller as a proportion of the national number than it was in 1900. The question my correspondant wonders about, though, dogs all discussion of economic progress -- does increased productivity actually mean that we are better off? Fortunately, that's not the subject of this post. Rather, we only want to honor the farmers who turned the land between the Missouri and the Mississippi rivers into some of the most productive on the planet.

Here are the horses:

2 Comments:

By SR, at Sun Sep 23, 08:47:00 PM:

It seems to be a fact of life that the end producer supplies less and less of the total value, the more technology enters the picture. I was talking with a friend of mine, a general surgeon who was lamenting the worsening re-imbursement . He said that more and more surgeons are being paid by hospitals for availability rather than for the actual surgery they do.

The money goes to the owners and intensive users of technology (as well the controllers of the patient flow- eg. insurers). Surgeons of the future will be using robots that will turn surgery into a video game.

By , at Mon Sep 24, 12:11:00 AM:

The trend of declining income and quality of life as technological progress pushes down the cost of production is, of course, a classic prediction of Marxist economics. Over time, industries become more and more capital intensive, which reduces the number of firms (in this case farmers) competing and thereby increases the amount of work each firm has to do. Income remains constant because as the cost of production goes down, so does the price of the product, and in corresponding amounts.

Of course now there's a movement back towards "natural" and "sustainable" food, which idolizes and attempts to recreate the old model of the small farm. It will be interesting to see whether our increasingly wealthy (and therefore increasingly able to pay higher food prices) nation decides to subsidize the antiquated way of farming.